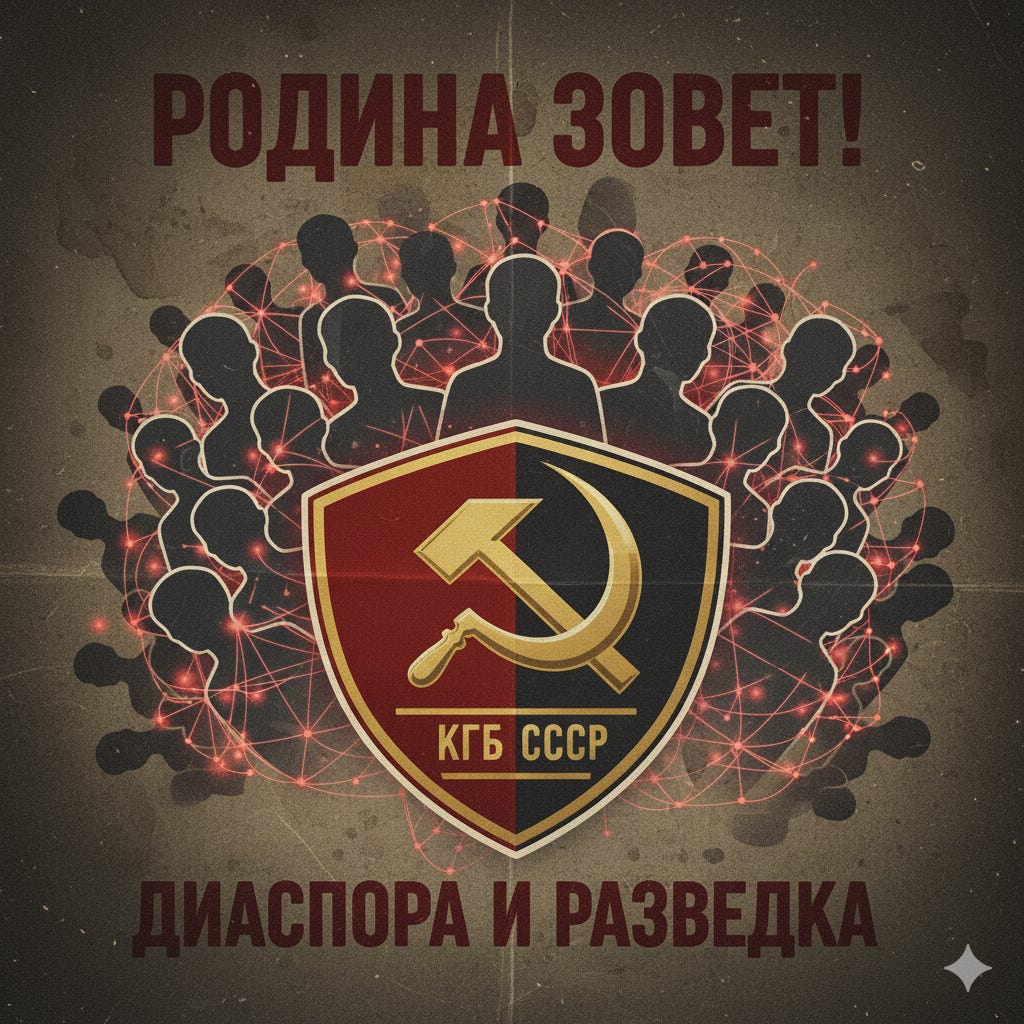

Inside Moscow's Compatriots Policy

How the KGB instrumentalized the Soviet diaspora for intelligence work

This manual, published in 1968, looks at how the Soviets used their diaspora for intelligence purposes, either as hostile objects to be spied on and destroyed from within, or as fertile terrain for recruitment in the advancement of Moscow’s strategic interests. Today, the Russian special services maintain this tradition. Pravfond, a state-backed Russian foundation that provides legal aid to Russian citizens abroad, is in fact a support network for spies, criminals and propagandists, as an investigation last year by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project discovered. Rossotrudnichestvo, the Russian Foreign Ministry’s “cultural” arm, is a clearinghouse for the SVR, Russia’s foreign intelligence service. And the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence service, leverages the Institute of Russian Diaspora, among other groups, for the prosecution of psychological warfare against the West.

The introduction for the English translation of this KGB training manual was written by Dr. Kevin Riehle, a friend and colleague of Foreign Office. Kevin is a lecturer at Brunel University London, and a 30-year veteran counterintelligence analyst in the U.S. government. He is the author of several magisterial books on the Soviet and Russian intelligence services, including a history of the FSB.

- Michael Weiss

The KGB believed that no anti-Soviet émigré group could exist without the assistance of a foreign intelligence service. It taught its officers that anti-Soviet national movements abroad were, by definition, nothing but tools that foreign intelligence services used to conduct ideological sabotage against the Soviet Union.

It is true that US and British intelligence services tried to employ some anti-Soviet émigré groups against the Soviet Union. They recruited members of the groups and tried to direct their anti-Soviet fervor in a desired direction. However, that effort waned by the late 1950s.

The KGB’s 1968 manual on using the Committee for Cultural Ties with Compatriots Abroad for Intelligence Purposes assesses that the reason for the reduction in Western intelligence use of anti-Soviet émigré groups was that the Soviet economy and society had developed so far that anti-Soviet groups were no longer as attractive as alternatives for émigrés. It was a self-congratulatory message to KGB officers, telling them that they were on the right side of history, and that Western intelligence services were failing.

The real reason for the reduction in Western intelligence services’ support was that anti-Soviet groups competed rather than banding together to achieve their common goal of removing the Soviet communist government. They could never agree on what should replace it and who would lead the follow-on regime. To some extent, KGB operations exacerbated that divisiveness.

The Soviet Committee for Cultural Ties with Compatriots Abroad was created in 1963 to replace post-World War II efforts to encourage emigrants abroad to repatriate. By 1963, most members of those groups were aware of what awaited them if they accepted repatriation offers, including, at best, isolation in remote regions of the Soviet Union, and, at worst, life in a corrective-labor camp. By 1963, the KGB needed to retool its repatriation policy to appeal to a more settled expatriate population.

Just as the KGB taught that anti-Soviet national groups could exist only with the support of Western intelligence services, pro-Soviet groups could exist only with the KGB’s support. The conversion of the expatriate population abroad to pro-Soviet needed a boost. When the 1968 manual was released, the KGB assessed that there were 150 anti-Soviet emigrant groups abroad that produced 78 newspapers and magazines. Pro-Soviet “progressive” groups, on the other hand, numbered only 55 and produced 27 newspapers and magazines. Those “progressive” groups needed ideological and financial support to overtake their competitors.

The KGB’s end goal was the “disintegration of anti-Soviet émigré centers and the paralysis of their subversive work, while simultaneously strengthening and expanding progressive patriotic movements and attracting both neutral and independent émigré circles to them” (p. 9). The Committee for Cultural Ties with Compatriots Abroad was the tool to accomplish that goal.

Imants Lešinskis, a Latvian KGB officer, was a player in the effort to steer expatriate national communities in a Soviet direction. He defected in New York City in 1979 and brought with him knowledge about how the KGB targeted specific émigré groups—in his case, Latvians—to discredit their anti-Soviet leaders and attract the rising generation with all-expenses-paid trips to their ancestral homeland and free publications that portrayed the Soviet Union in glowing terms. Lešinskis traveled around Europe for a mix of purposes: for outreach to émigré groups and to spot and assess potential candidates for KGB recruitment as intelligence sources. His activities reflected the operational doctrine in the 1968 manual on using the Committee for Cultural Ties with Compatriots Abroad for Intelligence Purposes.

The Russian Federation today retains the belief that any expression of anti-Russian views among expatriates must be the work of a foreign hand. That is manifested in Russia’s reactions to what have come to be called “color revolutions.” As far as Russian leaders are concerned, the popular overthrow of a pro-Russian government in places like Ukraine, Georgia, and Kyrgyzstan could only have happened with the support of a foreign power. They reflect a view that all global events are orchestrated by great powers, and by extension, smaller powers and their national identities are insignificant and have no agency. That view was shared both by the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation.

The Soviet-era Committee for Cultural Ties with Compatriots Abroad is now the Government Commission on Compatriots Living Abroad under the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It fulfills much of the same function as its Soviet predecessor. It is also a tool of Russian intelligence services to penetrate foreign émigré organizations and steer them in a pro-Russian direction. Consequently, the KGB’s manual remains valid today.

- Dr. Kevin Riehle.